Interview with Antonello Tolve

Simone Ciglia

In 2016, Quodlibet published Antonello Tolve’s La linea socratica dell’arte contemporanea. Antropologia Pedagogia Creatività (The Socratic line of contemporary art. Anthropology Pedagogy Creativity). The text, which is explicitly reminiscent of the critical legacy of Filiberto Menna, revolves around the connection between contemporary art and education.

The book is divided into three chapters. The first – Le declinazioni dell’educazione planetaria (The declinations of global education) – introduces issues linked to education in the present global scenario. The following chapter, Intervallo critico (Critical interval) examines the theme of art critique and its current crisis (with particular emphasis on curators). The third chapter, L’arte di insegnare con l’arte (The art of teaching with art) reviews a series of artistic figures that dealt with the educational themes typical of their field of expertise during the late ‘900s (Joseph Beuys, Piero Gilardi, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Marina Abramović, Giuseppe Stampone, Mónica Alonso, Pedro Reyes, Rosy Rox). The book ends with Epilogo socratico (Socratic epilogue), dedicated to artist Tomaso Binga.

Dear Antonello, your latest book, La linea socratica dell’arte contemporanea, is centred around the thematic links – made explicit in the subtitle – among Anthropology, Pedagogy and Creativity. What are the reasons underlying your reflection in this historical period?

As of late, social responsibilities are being assigned to artists based on social-anthropological lines and suffixes linked to education, pedagogy and andragogy. The reason why I have chosen to mingle anthropology, pedagogy and creativity stems from a wish to reinterpret a certain artistic scene from a more Socratic standpoint, linked to creators who focus not only on the creation of artworks, but also on their function, especially the educational and extracurricular one. Everything derives from the acknowledgement of the decline of education. If we think of great masters such as Giorgio Caproni, who taught in elementary school, or important artists who have enlivened academic institutions, we will immediately realise that something has changed, for better or worse. What is thus the function of Bildung in the current landscape? Is it to shape free citizens able to take care of their spaces?

Your critical reflection clearly draws inspiration from the work of Filiberto Menna and your mentor Angelo Trimarco. The title of your book explicitly quotes Menna’s fundamental text, La linea analitica dell’arte moderna (The analytical line of modern art). What does the new “Socratic” line that you have pinpointed consist in, and how is it linked to Menna’s work?

This question is particularly interesting and significant. Indeed, the title is reminiscent of the extraordinary book written by Filiberto Menna in the early ‘70s and published by Einaudi in 1975.

La linea analitica was and still is a fundamental and Socratic work to me, as is the entire reflection of Filberto Menna, who was my mentor’s mentor. The idea of using a title clearly reminiscent of Menna’s book is to be intended as a tribute and an intellectual compliment. However, rather than paraphrasing that line, I wanted to describe the direction of a pedagogical and andragogical attitude that I deem as central not only in today’s art, but also yesterday’s and tomorrow’s. The book is divided into three chapters. The second one, which I entitled Intervallo critico in order to recall the 2001 book L’arte e l’abitare (Art and inhabiting) by Angelo Trimarco, one of the most brilliant theorists of the late ‘900s, is dedicated to three people that I consider as paramount – Achille Bonito Oliva, Gillo Dorfles (a beloved friend who passed recently) and Trimarco himself – and able to represent the field of critique, which does not merely analyse artworks, but carefully reflects on all the paths that creativity and humanity itself embark upon.

In the book, you collected a series of artistic experiences that date back to the late ‘900s and range from Beuys, Gilardi, Abramović and Pistoletto to the younger generations, which include the likes of Pedro Reyes and Giuseppe Stampone. How did you select these authors? The presence of many Italian artists is worth noticing: do you think it is a cultural symptom?

Yes, I believe it is a cultural symptom. In Italy, technocracy has damaged, and in some cases deteriorated, the school system, leading it to an inevitable paralysis.

The artists that I have selected and included in the third section of the book are but samples of a larger Socratic scene. I tried to organise an itinerary whose stages, which I deem as paramount, enable – at least in my journey – one to pinpoint the Socratic behaviours of artists who transform art into an educational space, build upon education to turn it into an artwork, or experience art and education as a single entity. In this section of the book, which almost consists in the implementation of a theory, I tried to use the titles as a way of interacting with the reader (and looking for a missing dialogue). By carefully reading the various paragraphs dedicated to the included artists, it is indeed possible to find many references to Marcel Proust’s À la recherche.

Educational Turn is the denomination that emerged in the mid-90s to describe a series of – increasingly widespread – artistic practices revolving around cooperation and research processes and focusing on the overcoming of traditional educational structures. What is your stance towards this trend, and how does it fit into your discourse?

If we recall the beautiful book edited by Paul O’Neill & Mick Wilson (Curating and the Educational Turn, 2010), we will immediately realise that the pedagogical and didactic issues of art have become ever more significant. My stance is closely linked to John Dewey’s and to the idea of art as an experience. If we go back to some of his essential, prophetic theoretical writings, we will realise that during the 1930s people wanted to leave tradition behind and embrace a new kind of education, which was based on knowledge as it was on practice and was able to enhance singularities and – as Maria Montessori said – teach freedom.

Antonello Tolve studies the artistic trends and critical theories of the 1900s, with particular emphasis on the links among art, art critique and new technologies. He has published many essays in this field. He teaches at the Academy of Fine Arts of Macerata, and was visiting professor in various universities, such as the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University – Tc Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar Üniversitesi (Istanbul, Turkey), the GDUT – Guangdong University of Technology / Guăngdōng Gōngyè Dàxué (Guangzhou, China) and the BLCU – Beijing Language and Culture University / Běijīng Yŭyán Daxué (Beijing, China).

Biography

Antonello Tolve is an art critic and independent curator, he has been a member of numerous international panels, and has curated exhibitions that focus on the present of art and life with a visual and reflective approach of multidisciplinary and multilingual nature. His books include Gillo Dorfles. Arte e critica d’arte nel secondo Novecento (2011), ABOrigine. L’arte della critica d’arte (2012), Ubiquità. Arte e critica d’arte nell’epoca del policentrismo planetario and Esibizione dell’esibizione (2013).

Giuseppe Stampone, Global Education from Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, Seoul 2017, courtesy l’Artista.

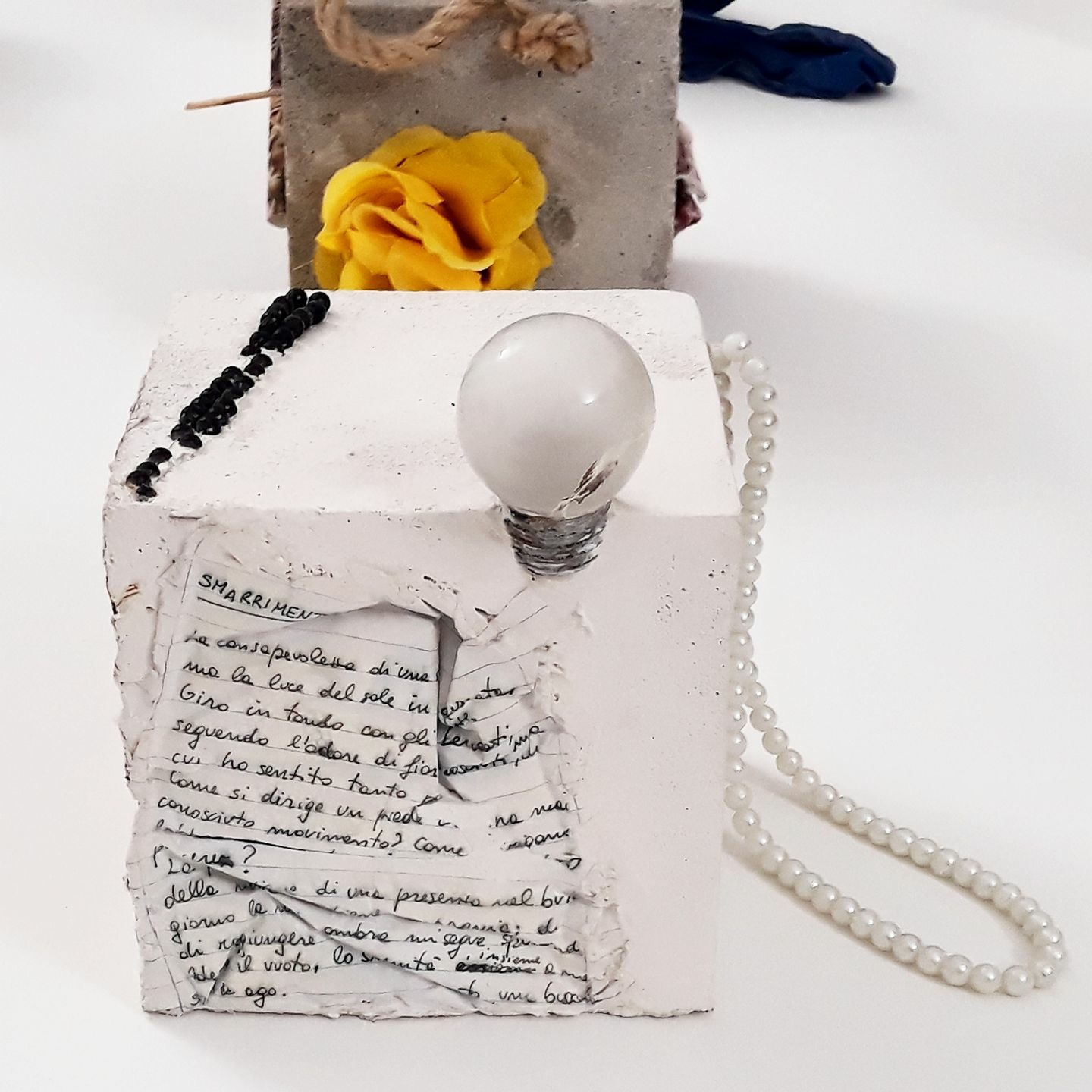

Rosy Rox, Il dono, 2018, exhibition view, Museo MADRE (Napoli), courtesy l’Artista.

La Piperita. Un progetto editoriale nato tra i banchi di scuola, 2012, meeting/workshop/exhibition with Ludovica Chiarandini and Vida Rucli, CRAC from Liceo Artistico Statale Bruno Munari (Cremona), curated by D. Ferruzzi and G. P. Machiavelli, Courtesy Archivio CRAC (Cremona).