Artists for Artists’ Sake: Notes on Independent Art

Sarrita Hunn

In order to define the ‘independent’ field of art, one must first recognize that there is no one artworld. That is of course true in infinite forms at the micro level, but one can also see this in a more general way at the macro level. I propose that for the last half century we have been operating across two distinct spheres, the commercial and academic art worlds, and are experiencing the distinct emergence of a third sphere – one that emerging organizations like The Independent (IT), Common Field (US), Common Practice Network (UK/US), and (to some extent) Arts Network Asia, and tranzit, attempt to bracket.

The market world of art production has of course existed for centuries in different forms, but the rise of an academic arena for art practice as a relatively new ‘field’ has a particular history over the last century. One could possibly trace this from the Bauhaus to Black Mountain College, through the rise of critical art writing by artists in the 70s and 80s, and finally to the overwhelming predominance of the MFA in the US and Art Practice PhD in Europe (alongside an expanding roster of MAs in anything from Curatorial Practice to Performance, bracketing an entire field of production within academia) in the last decades. Anyone who has worked in academia knows that success in that field is defined along slightly different terms than those of the market and vice versa. They are interrelated, of course, but it is easy today to forget the relatively newfound freedom allowed to artist-faculty to explore outside of commercial concerns through their support as academics. Think, for example, of the Los Angeles legacy of artist-professors such as Judy Chicago and John Baldessari, not to mention Joseph Beuys’ highly influential activities during and after his dismissal at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf that included founding the Free International University and the Green Party in Germany.

However, as academia has financialized (especially in the United States), these once somewhat separate fields are also losing their distinction. It is clear now the ways in which the academic realm has been co-opted by the market, and artists working in general have been required to embrace an increasing level of professionalization. To put it another way, it use to be said on the US East Coast you’ve ‘made it’ as an artists with you quit your teaching job and on the West Coast you’ve ‘made it’ when got one. In a world of an increasing number of self-identified artists who are neither ‘making it’ or getting (full-time) teaching jobs, these distinctions seem less relevant.

Conversely, as Institutional Critique has become academicized (particularly with so-called New Institutionalism in Europe, a theory that focuses on the sociological aspects of institutions, alongside the growing number of artistic practice and research-based PhDs), conversations around the social and political implications of independent art have increasingly lost their connection to an actual practice. There is a high level of discourse, but (in combination with public and private art funding that gives preference to socially-engaged initiatives) also surprisingly limited forms. To put it another way, I have noticed one of the first thing artists in (notably northern) Europe will tell you is whether they make work for grants or galleries, but in a world where the largest number of self-organized projects look a lot like white cube storefront commercial spaces (and art institutions are increasingly community-engaged), this distinction seem less relevant.

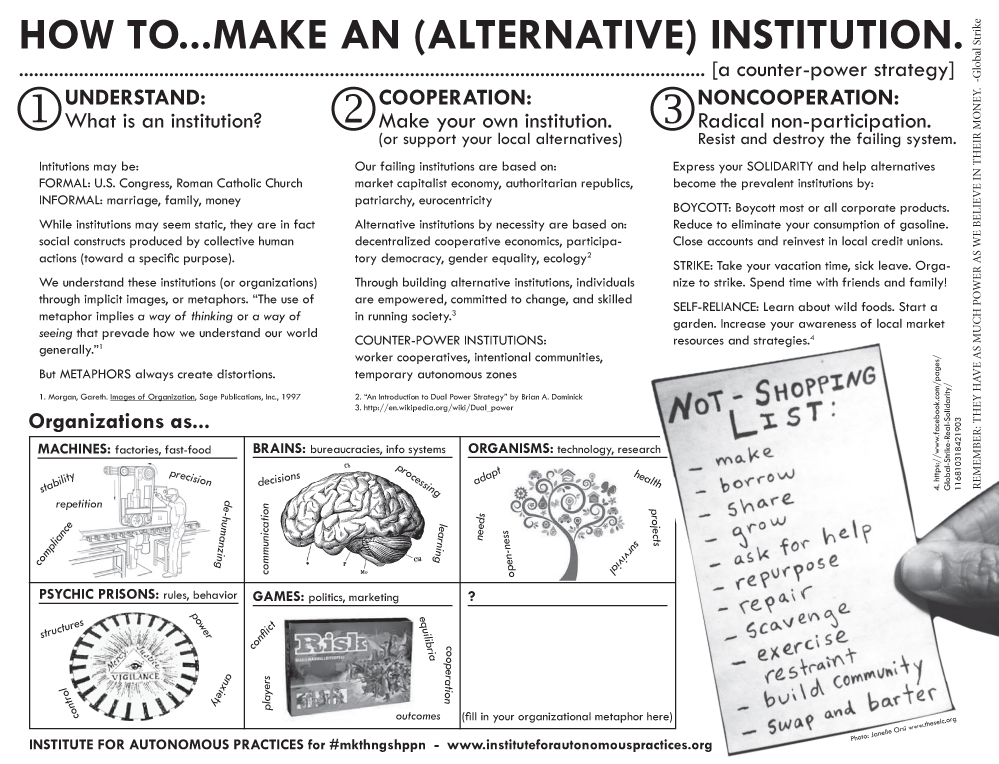

But a third way has emerged. It is notable that this third field first defined itself in the negation of the other two – the ‘alternative’ gallery and the ‘alternative’ school. However, this definition by negation has yet to be enough to carve out an entire ‘field’ on its own. This is not entirely new (we are arguably in a third wave of this practice, with the first in the early 1970’s and the second in the 1990’s), but a growing number of practitioners are aiming to formalize these efforts on their own terms. On a structural level, I would describe the field as ‘artists for artists’ sake’ – defined as consisting of those organizations (and artists, curators, administrators, etc.) working in the full range of independent, self-organized practices (from apartment galleries to artist-led and -centric nonprofits) who define their priorities and values in terms of artistic support and concerns (which by definition changes over time) and generally take the form of hybrid spaces and/or residencies, non-commercial galleries, and platforms for learning and sharing information. To be clear, I am not trying to reference an essentialist claim to ‘art for art’s sake,’ but the subversive potential of being subject (historically speaking) to neither church nor state.

I would characterize the independent field as being typically artist and/or curator-founded, and existing aside and/or in a fluid interrelationship with the market and academic fields, but also distinctly separate. For example, one may work as a faculty in a local art department or school, show in a commercial gallery and still run a project space out of their living room or studio. But the third field – the ‘independent’ field – is really concerning the latter, the realm in which priorities and values are determined by the artists/curators themselves, not the market or academia that may or may support them otherwise.

One may argue that institutionalizing this third ‘field’ may be the first step toward its cooptation, but that argument lies in the assumption that the market (particularly within neoliberal capitalism today) is an inevitability. This is the assumption that this third field must reject. Being hybrid in nature, artists are uniquely positioned to think both inside and outside the existing spheres. As Lise Soskolne stated for W.A.G.E. at a Common Field Convening (aka Hand-in-Glove) in 2015:

The exceptional status of the artist as someone working both inside and outside of capitalism, drawing from and working against, is something that we must both acknowledge and put to work. In other words, as artists we must acknowledge that our labor is not exceptional in its support and exploitation by a multi-billion dollar industry, while simultaneously putting our own exceptionality to work by engaging our own labor in political terms and as a political act – not as an artistic gesture.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, members and allies of this independent field must leverage what power we are given within the commercial and academic (and also increasingly civic) spheres as “cultural workers” to position ourselves outside, and in resistance to, these hegemonic power structures. As artist-centric institutions, this means using radical forms of participation to forefront self-organized, inclusive and equitable structures – this means creating new social imaginaries.

If our failing institutions are based on market-driven capitalist economy, authoritarian republics and eurocentricity – then our ‘alternative’ institutions by necessity must be based on decentralized cooperative economics, participatory democracy, equality, transnationalism and ecology. Through building this third field, artists become empowered, committed to change, and skilled in developing a society with these values. This is not (only) an artistic gesture but a matter of “engaging our own labor in political terms.” As Lise continued:

…it is only once we organized effectively around non-payment in our own field, that we can align ourselves with other workers struggles. Before we can align ourselves with other workers struggles, we must be prepared to occupy our own exceptionality, however uncomfortable, and as politically as possible.

For those of us looking to develop and define this third field let’s start by asking ourselves and each other: ‘What do I need?’ and ‘What can I give?’ With these priorities, we can avoid the financialization (and academicization) of the third field and define it on our own terms. We might not get everything we want, but we just might get what we need.

This essay has been adapted from the author’s Social Response to Hand-in-Glove 2015, “Artists for Artists’ Sake,” first published on Temporary Art Review October 19, 2015.

Sarrita Hunn is an interdisciplinary artist whose often collaborative practice focuses on the culturally, socially and politically transformative potential of artist-centered activity. She is co-founder/editor (with James McAnally) of Temporary Art Review, an international platform for contemporary art criticism that focuses on alternative spaces and critical exchange among disparate art communities. Recent projects include “Field Perspectives: Art Organizing within Accelerated Capitalisms” (with Miami Rail), a series of essays for the 2016 Common Field Convening (Miami, FL); To Make a Public: Temporary Art Review 2011-2016, a five year anthology published with Institute for Connotative Action (INCA) Press and distributed by Motto Berlin; Inter/de-pen-dence: the game (with Christine Wong Yap) performed at SOHO20 (Brooklyn, NY); and “Imagining Alternative Art Criticism” workshops at Pelican Bomb Gallery X (New Orleans, LA) and Louise Dany (Oslo, Norway). Additionally, she is the art editor for Exberliner, an English language print magazine in Berlin, Germany.